Wallens Ridge State Prison

Wallens Ridge State Prison

Big Stone Gap, VirginiaOur friends at

Appalshop asked us to review a documentary entitled

Up the Ridge recently, before it went on a viewing tour of many eastern Virginia cities. The movie is on the politics, economics, and social issues surrounding the building of the

Wallens Ridge State Prison of Big Stone Gap, Virginia in particular and those surrounding the building of Super-Max prisons and the commodization of prisoners. Specifically, my e-mail from Nick Szuberla gave the following overview:

Up the Ridge is a documentary film produced by Nick Szuberla and Amelia Kirby. In 1999, Szuberla and Kirby were volunteer DJ’s for the Appalachian region’s only hip-hop radio program in Whitesburg, KY when they received hundreds of letters from inmates transferred into nearby Wallens Ridge State Prison, the newest prison built to prop up the region’s sagging coal economy. The letters described human rights violations and racial tension between staff and inmates. Filming began that year and, through the lens of Wallens Ridge, the film offers viewers an in-depth look at the United States prison industry and the social impact of moving hundreds of thousands of inner-city minority offenders to distant rural outposts. Up the Ridge explores competing political agendas that align government policy with human rights violations, and political expediencies that bring communities into racial and cultural conflict with tragic consequences.Fine and dandy, eh? Well, that said, let me talk about some of what I consider to be the good points and bad points of this movie, in no particular order:

1. No matter where you’re from, this movie brings up some key points. How should super-maximum security prisons be used, and for what kind of offenders? The movie, for instance, points out that at the Wallens Ridge facility, educational books are disallowed, ostensibly as a punishment, but that pornographic and “trashy” literature is allowed. Frankly, I don’t know much about this facility, but if this is true, well, I can only say that I think the policy should be exactly the opposite. Plus, one must wonder if the process of deciding who does and does not get shipped to super-max prisons should be both transparent and, perhaps, even include public input in the form of an elected board of some sort.

2. This movie also brings up the enormous absurdity which is drug policy in our nation – punishments for drug-related charges are inordinately strict, stricter than rape and other violent crimes, often. Yet drugs are incredibly prevalent and virtually every American uses at least one illegal drug (or abuses an otherwise legal drug) at some point in their life. The system of dealing with drug use and sales, I think everyone would agree, simply does not work. I won’t go into my recommendations here, but there it is.

3. The movie brings up the fact that by shipping overwhelmingly black prisoners to an overwhelmingly white area, super-max prisons tend to reinforce both black and white stereotypes, increasing stereotypes.

4. What I think is a key point is demonstrated by this film, even if the filmmakers didn’t intend to show it. The families of prisoners and prisoners want protection in place against the culture of silence that prevails in correctional facilities, and understandably. Abuse and punishment are not synonyms. That said, these same people tend to complain about the lack of privacy in these facilities, about the omnipresence of video cameras. This is, frankly, an enormous, massive oxymoron. The one major improvement that could, and probably should, be made, is by making these films fully transparent to the public upon court order, with films stored outside of the prison facilities. Is it embarrassing? Yeah, but so are a great many other things whose utility outweighs their benefits.

5. Big, massive, huge point of the movie – Big Stone Gap, nice place that it is (and it is a nice place) is really far from eastern Virginia, where many of the prisoners come from, and really, really far from Connecticut, where several others, including two prisoners who died not long before the time of the film’s creation, come from. This means that if the families of the prisoners wish to visit prisoners, the cost is quite high – often extraordinary in relative terms when we consider that most people in prison come from families who are economically less successful than average. I haven’t decided how I feel about this in principle, honestly, given that, under the current practical conditions shipping of prisoners is almost a necessary condition, but I can say that I believe some sort of public dialogue is warranted. Do the citizens have a right not only to a trial by their peers but also to a punishment by their peers?

6. This film presents the guards as real human beings, just trying to make a living and improve their economic condition by taking a hard job that most people, frankly, don’t want. These people are, frankly, taking risks. Indeed, even some of the most effective critics of the prisons are former guards. The people of Big Stone Gap, in other words, are presented as people in a coal/tobacco town trying to take advantage of an economic opportunity.

7. I teach my students about “iron triangles,” such as the military-industrial(-elected official-intelligence) complex – political assemblages in which different private and public groups manipulate taxpayer sentiments to guarantee political and economic benefits to everyone in the assemblage at taxpayer expense – not to mention the soldiers who fight the wars. This film adds another intriguing iron triangle – the corrections-industrial(-elected officials) complex.

8. This film’s big failings? Well, they are two-point. First, the film is critical of the prison system, defending prisoner’s rights, without ever bringing up the crimes these prisoners committed either before imprisonment or during their prior imprisonment that justified their being sent to a super-max facility in the first place. This might just matter. Second, the families of prisoners complain about the fact that prisoners are shackled prior to and during meetings and that they are searched as the enter the prison. Frankly, I didn’t see the need to harp on this point – it is a secure facility. That’s just how life is.

In the end I think this is a solid documentary, really worth a gander. You may not agree with all its points, but I’ll make you think about a plethora of important issues, and it’s a great example of how the influx of new wealth into any small town can have radical consequences, for better and for worse.

Well, all that said, producer Nick Szuberla asked me to post some locations and dates of screenings. So here are some. Screenings.

Oct. 2nd Newport News, VA (7pm) Christopher Newport University, Ferguson Center for the Arts, 1 University Place

Oct. 3rd Roanoke, VA (7pm) Blue Ridge Public Television, 1215 McNeil Drive

Oct. 4th Charlottesville, VA (7pm) Sojourners United Church of Christ, 1017 Elliot Ave

Oct. 5th Alexandria, VA (to be announced)

Oct. 6th Richmond,VA (7pm) Wesley Memorial United Methodist Church, 1720 Mechananicsville Turnpike

Oct. 7th Norfolk, VA (to be announced)

Oct. 8th Harrisonburg, VA (2pm) Eastern Mennonite University, 1200 Park Road

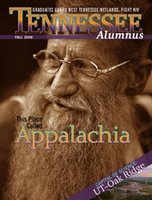

I have decided that I want to post five (Arabic numeral 5, Roman numeral V) vaguely Appalachian-themed sites for your consideration. Enjoy them. Or don't.

I have decided that I want to post five (Arabic numeral 5, Roman numeral V) vaguely Appalachian-themed sites for your consideration. Enjoy them. Or don't.