Appalachian Stereotypes in Art (Part 1)

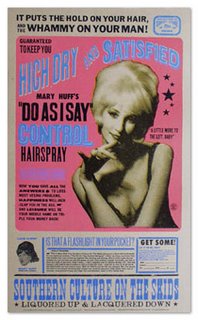

"She's liquored up,

And lacquered down.

She’s got the biggest hair in town.

She’s liquored up,

And lacquered down.

Me and my baby gonna paint the town.”

-Southern Culture on the Skids

Some take these faulty ideas and use them to create art. These artists in various forms highlight and broadcast this widely-accepted and misunderstood imagery of

Are these artists doing an injustice to Appalachian culture by perpetuating these stereotypes, or are they merely pointing out the absurdity of these ideas? Does spreading the image of an

In 1996, Julie Belcher and Kevin Bradley started a printmaking company in a barn in

In its ten years, Yee-Haw has created all sorts of different wares, from wedding invitations to advertisements for nationally-known rock and roll bands and

While not all of their work fits neatly into this old-fashioned block-letter style (some is highly abstract, with no text), many of the more popular pieces do. Peruse through Yee-Haw’s studio-front store and you will find posters and prints advertising artists like Lucinda Williams, Bill Monroe, Otis Redding, Bill Monroe, Johnny Cash and Loretta Lynn. While not all of these musicians are Appalachian per se, they are all in general embraced in the American South, and mostly recognized as Southern artists. Similarly, Bradley and Belcher are not artists that pursue strictly Appalachian themes, but their work certainly has the flavor of the region.

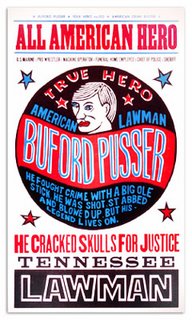

One way that Yee-Haw displays its Appalachian-ness is through imagery. Many of the figures in their work are meant to represent a specific - usually famous – person, but nearly all of these illustrations amount to a generic mock up more than they are caricatures. What is interesting is that they end up looking like characters borrowed from the telling of any Appalachian folk tale. This is part of the charm of Yee-Haw’s work; Hank Williams doesn’t have to look like Hank Williams for the piece to be effective.

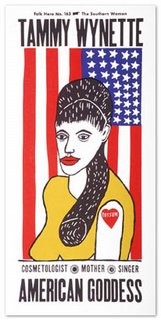

Take the poster at left featuring Tammy Wynette. Without the bold typeface announcing the character’s identity at the top, no one would recognize this figure for who it represents (first of all, Tammy Wynette was blonde). Still, taken as a whole, the poster is a fitting tribute to the singer and writer of “Stand By Your Man.” It is worth noticing the bun hairdo and bold red lipstick. Notice also the allusion to Wynette’s marriage and decades-long romance with country crooner George Jones. It is represented by a simple heart-shaped arm tattoo with Jones’s nickname written inside: “POSSUM.” Finally consider the red-state patriotism expressed by putting the image of Wynette in front of an American flag. This is a symbol that recurs in Yee-Haw’s work. Overall this piece throws back to several symbols that are often associated, right or wrong, with

Take the poster at left featuring Tammy Wynette. Without the bold typeface announcing the character’s identity at the top, no one would recognize this figure for who it represents (first of all, Tammy Wynette was blonde). Still, taken as a whole, the poster is a fitting tribute to the singer and writer of “Stand By Your Man.” It is worth noticing the bun hairdo and bold red lipstick. Notice also the allusion to Wynette’s marriage and decades-long romance with country crooner George Jones. It is represented by a simple heart-shaped arm tattoo with Jones’s nickname written inside: “POSSUM.” Finally consider the red-state patriotism expressed by putting the image of Wynette in front of an American flag. This is a symbol that recurs in Yee-Haw’s work. Overall this piece throws back to several symbols that are often associated, right or wrong, with

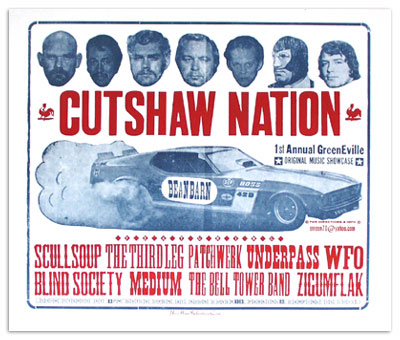

Consider also the poster below advertising a Greeneville rock and roll festival, Cutshaw Nation. While Bradley and Belcher did not give the festival its name, they certainly rolled with the idea when they were commissioned for the poster. Locals would know that the name Cutshaw is often associated with several working-class and notoriously rowdy families in the community. Again, this is certainly a terribly unfair stereotype. Having the Cutshaw surname no more damns a person to a lack of education and runs-in with the law than the name Rockefeller guarantees a life of privileged, blue-blood excess. The festival was so named in order to invoke thoughts of a gathering of people united in the pursuit of loud, drunken tomfoolery.

Two pieces of imagery stand out here. Most obviously is the muscle car set in the center of the layout, spinning its tires and flinging dust in rapturous hell-raising glory . The oval cutout in the middle of the car’s door panel contains the words, “Bean Barn,” the name of a famous burger joint in Greeneville (other printings of the poster feature the word “Edgemont,” a well-known local gas station where many 13-year olds probably bought their first pack of cigarettes). Along the top of the poster are cutouts of the heads of various former professional wrestlers. Both of these pieces of imagery bring to the fore ideas that fall in with stereotypical

. The oval cutout in the middle of the car’s door panel contains the words, “Bean Barn,” the name of a famous burger joint in Greeneville (other printings of the poster feature the word “Edgemont,” a well-known local gas station where many 13-year olds probably bought their first pack of cigarettes). Along the top of the poster are cutouts of the heads of various former professional wrestlers. Both of these pieces of imagery bring to the fore ideas that fall in with stereotypical

Text is also a major part of Yee-Haw’s work. Some of their work features a few words, some quite a lot (still yet, many pieces feature almost only text). Typical Yee-Haw verse is a kind of hillbilly-stream-of-consciousness style.

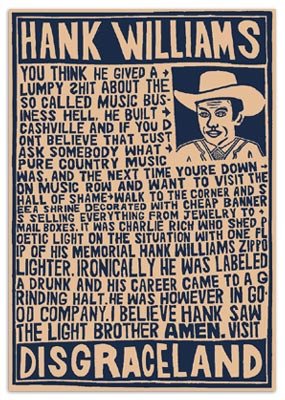

In this particularly funny print about Hank Williams, Sr., Yee-Haw artists imitate the language of the stereotypical Appalachian redneck. Notice especially the opening line, which reads perfectly like the start of a know-it-all hurangue: “You think he gave a lumpy shit about the so-called music business hell.” In reading the line, it is easy to imagine it in the voice of self-described hillbilly Billy Bob Thorton, or perhaps in the character of Boss Hog. Also, the penultimate sentence is a particularly interesting mimic of the stereotypical Appalachian: “I believe Hank saw the light brother Amen.” This tribute to the Bible Belted part of Southern

In this particularly funny print about Hank Williams, Sr., Yee-Haw artists imitate the language of the stereotypical Appalachian redneck. Notice especially the opening line, which reads perfectly like the start of a know-it-all hurangue: “You think he gave a lumpy shit about the so-called music business hell.” In reading the line, it is easy to imagine it in the voice of self-described hillbilly Billy Bob Thorton, or perhaps in the character of Boss Hog. Also, the penultimate sentence is a particularly interesting mimic of the stereotypical Appalachian: “I believe Hank saw the light brother Amen.” This tribute to the Bible Belted part of Southern

This use of stereotypical Appalachian language pairs nicely with the illustrations that lampoon hillbilly white-trash culture. White trash is exactly what Yee-Haw presents so effectively in its art. It may be unfair, but it communicates a sentiment that is in essence true. While

In the next part, we will take a look at a

2 comments:

Like I said before, excellent post. Great subject material and well written.

Looking forward to part deux.

John, looking forward to the second part! I am comfortable enough with my sexuality to say that you have a very pleasant writing style.

--DW

Post a Comment